From the Illinois Policy Institute comes this analysis of the inability of Springfield legislators to thoughtfully consider appropriations bills:

Lawmakers in the Illinois General Assembly must read fast when they get final state budgets, because thousands of pages are dropped on them at the last minute before they must vote.

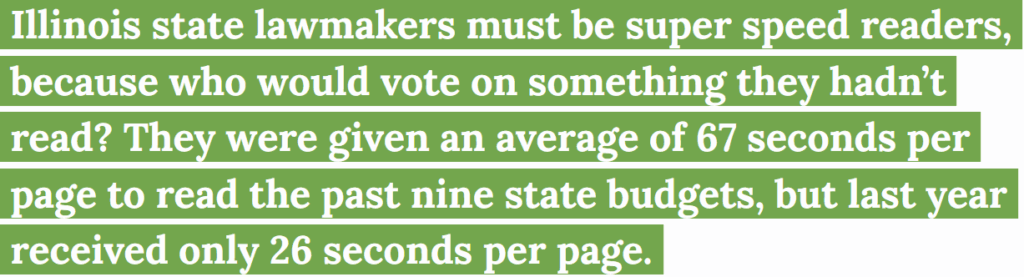

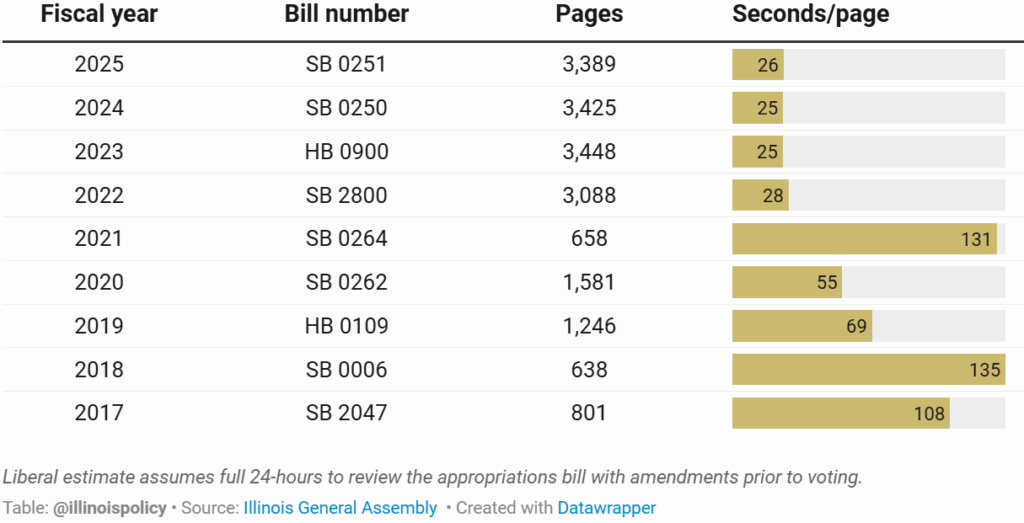

They averaged about 67 seconds per page to digest the past nine state appropriations bills. For the past four years they had less than 30 seconds per page to read over 3,000 pages.

Evelyn Wood would be proud.

Since fiscal year 2017, they read 18,274 pages of state budget appropriations bills – not including later fixes. It was easier in 2016 when the budget bill was just 11-pages because of the standoff between former Illinois House Speaker Mike Madigan and Gov. Bruce Rauner.

Reading a bill before voting on it would imply state lawmakers are acting in their constituents’ best interests and serving as taxpayer watchdogs. It would also imply they respected their constituents’ right to review and comment on the budget. The truth is they have only a faint idea how they are spending other people’s money, getting the CliffsNotes version from their leaders.

Lawmakers have long employed the practice of gutting insignificant bills and replacing the language with the operating appropriations bill’s substance at the last minute. They do so to get around the Illinois Constitution’s mandate that no bill get shoved through, but rather be read into the record on three separate days.

In fact, passing appropriations bills at the last minute makes the job so much easier when the public and most state lawmakers don’t know what’s really going on. No debate. No questions. No time to really understand the state budgets. That trusting acquiescence has long been the norm in Illinois and gets worse each year.

Lawmakers in the Illinois Senate approved the operating appropriations bill for the 2025 state budget on the last day of the legislative session. The vote came hours after adopting an amendment to the legislation that swapped out the original text of the two-page bill with 3,389 pages of appropriations set to go into effect July 1, 2024.

This allowed lawmakers to circumvent the rule requiring bills to be read on three separate days by replacing the language of a bill read twice already on the floor with the substance of the budget bill. It gave Senate members less than 26 seconds to review each page of the bill funding state operations for the coming year.

But that’s only if lawmakers read non-stop for a full day. It’s likely lawmakers had even less time to review the crucial budget bills as these estimates for past nine state operating appropriations bills generously assume lawmakers had 24 hours to review the legislation in its final form before being asked to vote.

Short-circuiting the bill reading process

The Illinois Constitution has provisions to prevent rushed legislation. Article IV, Section 8 of the constitution requires each bill be read on three separate days before it can be passed into law so lawmakers can know what they are voting for. Bills filed are read aloud “by title,” meaning the name of the bill must be read into the record. The full text of the bill need not be.

The purpose of this provision is to give all lawmakers a chance to know the substance of the bills before they take a vote and give voters time to become informed on the proposed legislation. But the spirit of this provision is often subverted through the practice of gutting and replacing legislation, often using shell bills that contain no real substance.

For example, Illinois’ entire fiscal year 2022 budget was originally introduced as a shell bill that read as follows: “The amount of $2, or so much of that amount as may be necessary, is appropriated from the General Revenue Fund to the Office of the State Appellate Defender for its FY 22 ordinary and contingent expenses.”

Lawmakers passed the bill in the Senate and went through two readings in the House before gutting and replacing it with all 3,088 pages of the budget at the third and final reading – leaving lawmakers with zero chance of reading, much less comprehending, the language they were expected to vote on.

That bill ended up riddled with errors, one of which would have prevented appropriations from being spent until a month before the fiscal year would end.

Gov. J.B. Pritzker was forced to issue an amendatory veto to correct the error.

The Illinois Supreme Court ruled that even if the letter of the law is violated, the legislation is not invalidated under the enrolled-bill doctrine. The high court deferred to the leaders of the state House and Senate to determine whether all procedural requirements for passage have been met – essentially granting the legislature the power to police itself.

Budgets are typically hundreds – and sometimes thousands – of pages, and lawmakers should respect taxpayers enough to know exactly where the money will be spent and be transparent about it before agreeing to appropriate state funds. But the ability to read bills before they are passed is just as important to everyday citizens, if not more so.

Other states prohibit gut-and-replace legislation

The Illinois legislature’s warping of its bill-reading duty should end. It is not the norm. For example, New York explicitly requires bills to be read in their final form in order to comply with its reading requirement. Idaho’s supreme court ruled their three-day reading provision implied a requirement that a whole bill as amended must be read on three separate days.

Pennsylvania’s supreme court ruled shell bills cannot be used to circumvent its constitutional reading requirement. And Alaska requires the three-readings timeline to start over if an amendment changes the substance of the bill.

In 2021 the good government groups League of Women Voters and Common Cause successfully sued to stop gut-and-replace legislation in Hawaii. In its decision, the Hawaii Supreme Court held the state constitution’s three-day reading requirement “necessitates that the substance of a bill must bear some resemblance to earlier versions in order to constitutionally pass the third and final reading.”

A real three-day reading requirement would help the public hold lawmakers accountable

Illinois has no real protections against lawmakers voting on bills in which they have a conflict of interest, and voters are reliant on lawmakers’ own statements of economic interest and on journalists and good government advocates to hold legislators accountable for their votes. Part of holding lawmakers accountable should be the ability to highlight conflicts of interest before a law is passed, and the state’s spending plan for the year is certainly a place where self-interest could arise.

Activists can highlight ethical lapses after a bill is passed, and there is often some period between passage in one chamber of the General Assembly and passage in the other chamber and delivery to the governor. But when bills are rushed through, watchdogs are given no opportunity to provide critiques.

Illinois should follow the lead of states such as Hawaii and New York. The legislative process should reflect the spirit of the Illinois Constitution and provide lawmakers and voters the opportunity to review the bills that will be voted into law before they pass, especially bills that spend voters’ taxes.

The intent of the constitution should be reflected in the law by granting lawmakers and taxpayers ample time to review legislation before its passage. This could mean a constitutional amendment that stops a rushed vote on a bill that has been gutted-and-replaced without the approval of a supermajority of members of the chamber. This requirement could also be a state law, or even listed in the House and Senate rules.

However it is done, Illinois voters deserve legislation that has been thoroughly reviewed, vetted and debated by the members they elected to represent their interests.

= = = = =

When budget bills were dropped on my desk or into my computer, I would start reading from the last page forward, assuming, often correctly, that the worst proposals were inserted in the back of the huge bill.